Details—Air travel may be fast and convenient, but exhaust from the millions of flights that take-off and land each year worldwide is having an impact on the health of the planet.

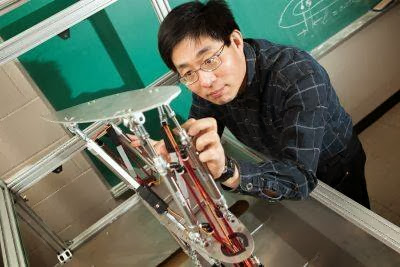

Fortunately, a Ryerson researcher is studying how to make airplanes more environmentally friendly. A professor of aerospace engineering, Fengfeng (Jeff) Xi has received funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada to support his work with "morphing" aircraft wings. Traditional aircraft wings are stationary, in contrast to Xi's shape-shifting wing. That is, other than high-lift devices such as flaps and slats that open and close, conventional wings remain in a fixed shape during all stages of flight – take-off, ascent, cruising, descent and landing. But this is not aerodynamically optimal, says Xi.

"A fixed geometry wing is not effective at reducing drag," he says. And when an aircraft experiences more resistance in flight, it uses up more fuel and this, in turn, generates more air pollution. And those emissions in the upper atmosphere not only contribute to climate change, but also eventually cause premature deaths on terra firma.

According to a 2010 study by researcher Steven Barrett of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, toxic pollutants in airplane exhaust kill at least 10,000 people around the world on an annual basis. Many of the deaths that are due to air pollution, reports the World Health Organization, involve cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, such as lung cancer. Clearly, the stakes are high, especially in light of the growing dependence on air travel. For example, according to the United States' Federal Aviation Administration, global air travel is expected to almost double by 2032. To help address the need for green aviation, Xi has partnered with undergraduate students, graduate students and faculty collaborators, including Paul Walsh, chair of aerospace engineering, to develop a prototype for a modular aircraft wing – one that makes use of lightweight materials, and can transform its shape to suit the unique aerodynamic demands of each stage of flight. The result: less drag, decreased fuel consumption and reduced emissions.

The team has filed a patent for its innovative, "variable geometry" wing design in the United States. Consisting of multiple movable sections that are supported by strong beams running the length of the wing, the technology is operated by onboard computers that monitor in-flight conditions. Those computers direct the wing's modules to adapt as needed, changing shape and creating new configurations in order to make the wing more aerodynamic. To date, the prototype has undergone testing in Xi's Reconfigurable System Laboratory in Ryerson's George Vari Engineering and Computing Centre. In the future, Xi plans to put the wing to the test in a large-scale wind tunnel.

Fortunately, a Ryerson researcher is studying how to make airplanes more environmentally friendly. A professor of aerospace engineering, Fengfeng (Jeff) Xi has received funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada to support his work with "morphing" aircraft wings. Traditional aircraft wings are stationary, in contrast to Xi's shape-shifting wing. That is, other than high-lift devices such as flaps and slats that open and close, conventional wings remain in a fixed shape during all stages of flight – take-off, ascent, cruising, descent and landing. But this is not aerodynamically optimal, says Xi.

"A fixed geometry wing is not effective at reducing drag," he says. And when an aircraft experiences more resistance in flight, it uses up more fuel and this, in turn, generates more air pollution. And those emissions in the upper atmosphere not only contribute to climate change, but also eventually cause premature deaths on terra firma.

According to a 2010 study by researcher Steven Barrett of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, toxic pollutants in airplane exhaust kill at least 10,000 people around the world on an annual basis. Many of the deaths that are due to air pollution, reports the World Health Organization, involve cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, such as lung cancer. Clearly, the stakes are high, especially in light of the growing dependence on air travel. For example, according to the United States' Federal Aviation Administration, global air travel is expected to almost double by 2032. To help address the need for green aviation, Xi has partnered with undergraduate students, graduate students and faculty collaborators, including Paul Walsh, chair of aerospace engineering, to develop a prototype for a modular aircraft wing – one that makes use of lightweight materials, and can transform its shape to suit the unique aerodynamic demands of each stage of flight. The result: less drag, decreased fuel consumption and reduced emissions.

The team has filed a patent for its innovative, "variable geometry" wing design in the United States. Consisting of multiple movable sections that are supported by strong beams running the length of the wing, the technology is operated by onboard computers that monitor in-flight conditions. Those computers direct the wing's modules to adapt as needed, changing shape and creating new configurations in order to make the wing more aerodynamic. To date, the prototype has undergone testing in Xi's Reconfigurable System Laboratory in Ryerson's George Vari Engineering and Computing Centre. In the future, Xi plans to put the wing to the test in a large-scale wind tunnel.

.jpg)